Rethinking LLM Security: Why Static Defenses Fail Against Adaptive Attackers

Hisham Mir

January 15, 2026

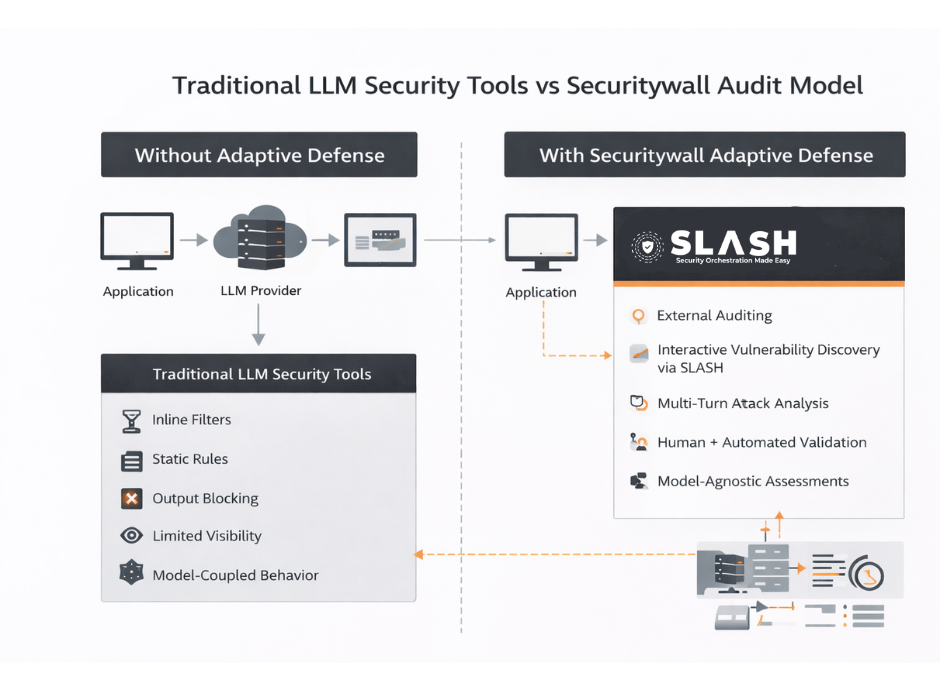

Large Language Model (LLM) security has become a critical concern as organizations deploy AI systems into production environments that handle sensitive data, internal workflows, and user-facing logic. While many teams rely on prompt filtering, content moderation, or policy-based guardrails, these approaches often fail against real threats. Modern LLM attacks are adaptive and multi-turn, exploiting the interactive nature of language models rather than a single unsafe response.

LLMs is less about blocking disallowed outputs and more about controlling how information is revealed across interactions a shift that requires fundamentally rethinking LLM security architecture.

When organizations first deploy large language models, the security model often feels deceptively simple. Add filters. Define policies. Block disallowed outputs.

Most deployed defenses assume a stateless model:

prompt → policy check → response

Attackers do not operate statelessly.

In internal testing, >80% of successful jailbreaks required multi-turn adaptation, where earlier failures informed later prompts. Treating each prompt independently discards the most important signal: attacker learning.

Yet in practice, even well-resourced teams find themselves reacting to a growing list of prompt injections, jailbreaks, and multi-turn manipulation strategies. The rules expand, but the attack surface expands faster.

At Securitywall, this tension raised an uncomfortable question early in our research that if LLMs are dynamic systems interacting with adaptive humans, why are we defending them with static assumptions?

That question forced us to look beyond conventional guardrails.

The Core Mismatch - LLMs Are Interactive, Defenses Are Not

LLM attackers optimize strategies, not prompts. Most LLM security controls treat each prompt as an isolated event. A single request is evaluated, filtered, and either allowed or rejected.

Attackers don’t operate this way. LLM attackers optimize strategies, not prompts. We model an attacker as an optimizer with feedback:

while not success:

prompt = mutate(previous_prompt, system_response)

response = model(prompt)

update_strategy(response)

Key properties:

- Observes refusal patterns

- Infers policy boundaries

- Exploits consistency gaps across turns

Any defense that reveals boundary information accelerates convergence.

This reframes security as controlling information leakage across turns.

In our internal red-team simulations, adversarial users treated the model as a conversational system they could probe, refine, and manipulate over time. Failed attempts were not failures they were signals. Each rejection taught the attacker something about where boundaries existed.

Once we framed the problem this way, it became clear that improving keyword filters or adding more policy text would never close the gap.

It raised a deeper design question: what would it mean for a defense to participate in the interaction?

Security as an Adversarial Interaction, Not a Classification Task

Traditional safety systems ask a binary question: Traditional safety systems ask a binary question: Is this prompt allowed?

Adversarial security asks a different one: What is the attacker trying to learn right now?

In our experiments, successful jailbreaks rarely came from a single malicious prompt. They emerged from sequences clarifying questions, reframing attempts, and gradual escalation.

This suggested that LLM security should not be modeled as content moderation, but as an adversarial interaction loop where intent, strategy, and learning evolve over time.

Once we adopted this framing, we stopped thinking in terms of “blocking” and started thinking in terms of control of interaction dynamics.

That shift unlocked a new class of defensive mechanisms.

Deception as a Defensive Control, Not a UX Trick

Deception in this context is not about lying to users. It is about controlling adversarial learning.

A defensive response is deceptive if it:

- Appears legitimate

- Does not advance attacker goals

- Does not confirm detection or policy boundaries

Conceptually, the system shifts from:

allow / deny

to:

advance / stall / misdirect

Example response strategy (simplified logic):

if interaction_is_probing(context):

respond_with(

plausible=True,

low_specificity=True,

no_operational_detail=True

)

else:

respond_normally()

Attackers cannot distinguish between:

- partial success

- misunderstanding

- intentional misdirection

This uncertainty is what increases attack cost. But deception cannot be bolted on. It requires structure.

A Multi-Agent Defensive Architecture for LLM Security

Static safety layers struggle because they attempt to do everything at once.

Our internal approach decomposes defense into specialized roles, each with a narrow responsibility.

We prototyped a multi-agent security layer composed of four cooperating components:

| Interaction Monitor | → detects probing patterns |

|---|

↓

| Misdirection Engine | → crafts deceptive responses |

|---|

↓

| Trace Analyzer | → tracks escalation trajectories |

|---|

↓

| Strategy Orchestrator | → adapts defense policy |

|---|

Each component is independently testable, but collectively they behave like an adaptive defense system rather than a rule engine.

This modularity turned out to be critical when it came time to evaluate effectiveness as architecture matters more than prompt wording.

We implemented defense as cooperating agents, each with a single responsibility. No agent enforces policy alone.

User

↓

| Interaction Monitor | |

|---|---|

| detects probing | |

| tracks turn patterns |

↓

| Misdirection Engine | |

|---|---|

| crafts safe but | |

| non-advancing replies |

↓

| Trace Analyzer | |

|---|---|

| tracks escalation | |

| identifies persistence |

↓

| Defense Orchestrator | |

|---|---|

| adapts response style | |

| escalates deception |

↓

LLM

Why This Works

- Stateful across turns

- Model-agnostic

- Adaptable without retraining

- Hard for attackers to fingerprint

Defense becomes an interaction strategy, not a rule set.

Measuring Security When “Correctness” Is the Wrong Metric

Accuracy metrics fail in adversarial contexts because the attacker’s goal is not correctness it is extraction.

To evaluate our defenses, we introduced metrics that reflect attacker experience rather than model output quality:

- Attack Progression Delay (APD):

How many interaction steps are required before an attacker reaches a meaningful exploit attempt. - Deception Retention Rate (DRR):

How long attackers continue engaging under false assumptions. - Resource Amplification Factor (RAF):

The increase in attacker effort relative to baseline defenses.

These metrics revealed something surprising:

even when attackers eventually succeeded, delaying and misdirecting them dramatically reduced real-world risk by increasing cost and reducing scalability.

This reframed success away from “perfect prevention” toward economic deterrence.

Which led to an important realization about deployment.

6. Attack vs Defense Flow (Side-by-Side)

Without Adaptive Defense

Attacker → Prompt

← Refusal

Attacker → Rewrite

← Partial Refusal

Attacker → Roleplay

← Exploit Success

With Adaptive Defense

Attacker → Probe

← Plausible Response

Attacker → Escalate

← Non-advancing Output

Attacker → Reframe

← Context Drift

Attacker → Abandon / Stall

The goal is not to block, it is to break attacker optimization loops.

From Guardrails to Security Engineering

LLMs are interactive systems exposed to adversaries.

Static rules assume static threats. Attackers are not static.

Effective defense:

- Controls interaction dynamics

- Limits information gradients

- Actively degrades attacker learning

This is not content moderation. It is adversarial systems engineering.

Once defense is designed this way, secure deployment boundaries expand dramatically and AI systems become viable in environments previously considered too risky.

The Path Forward: Adaptive, Strategic AI Defense

The future of LLM security will not be defined by longer blocklists or stricter refusals. It will be defined by systems that understand attackers as participants in a game of information.

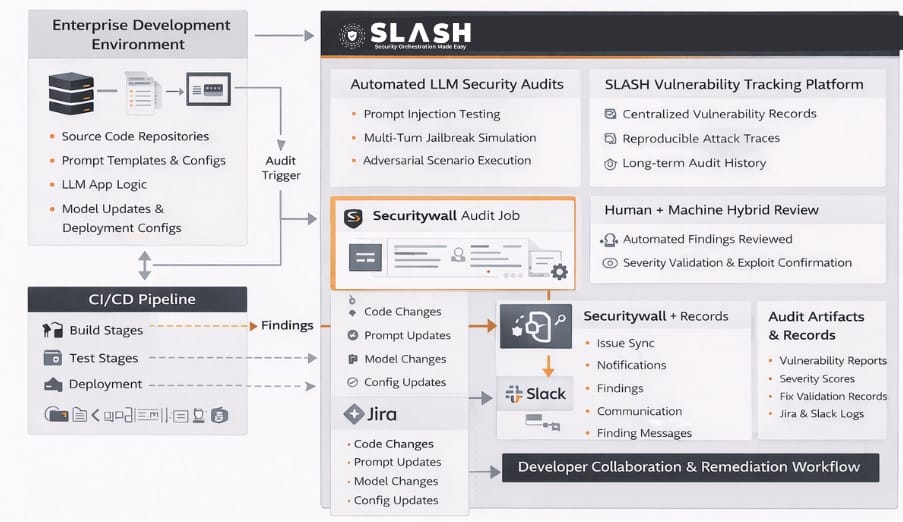

At Securitywall, this perspective is shaping how we design, test, and deploy AI defenses not as constraints, but as active systems that learn, adapt, and impose cost.

The implications extend beyond security. They influence trust, reliability, and how confidently organizations can deploy AI at scale and we are only beginning to explore what becomes possible once defenses stop standing still. Attackers disengage when feedback stops being useful.

Tags

About Hisham Mir

Hisham Mir is a cybersecurity professional with 10+ years of hands-on experience and Co-Founder & CTO of SecurityWall. He leads real-world penetration testing and vulnerability research, and is an experienced bug bounty hunter.